The journey of the gold rush that began in Alaska spread to the Sierra Nevada Mountains in California, New Zealand’s Otago Province, South America’s Patagonia, and Finland’s Arctic Circle. The common denominator of all these places where gold veins were found was that in the 19th century, they were uninhabited lands.

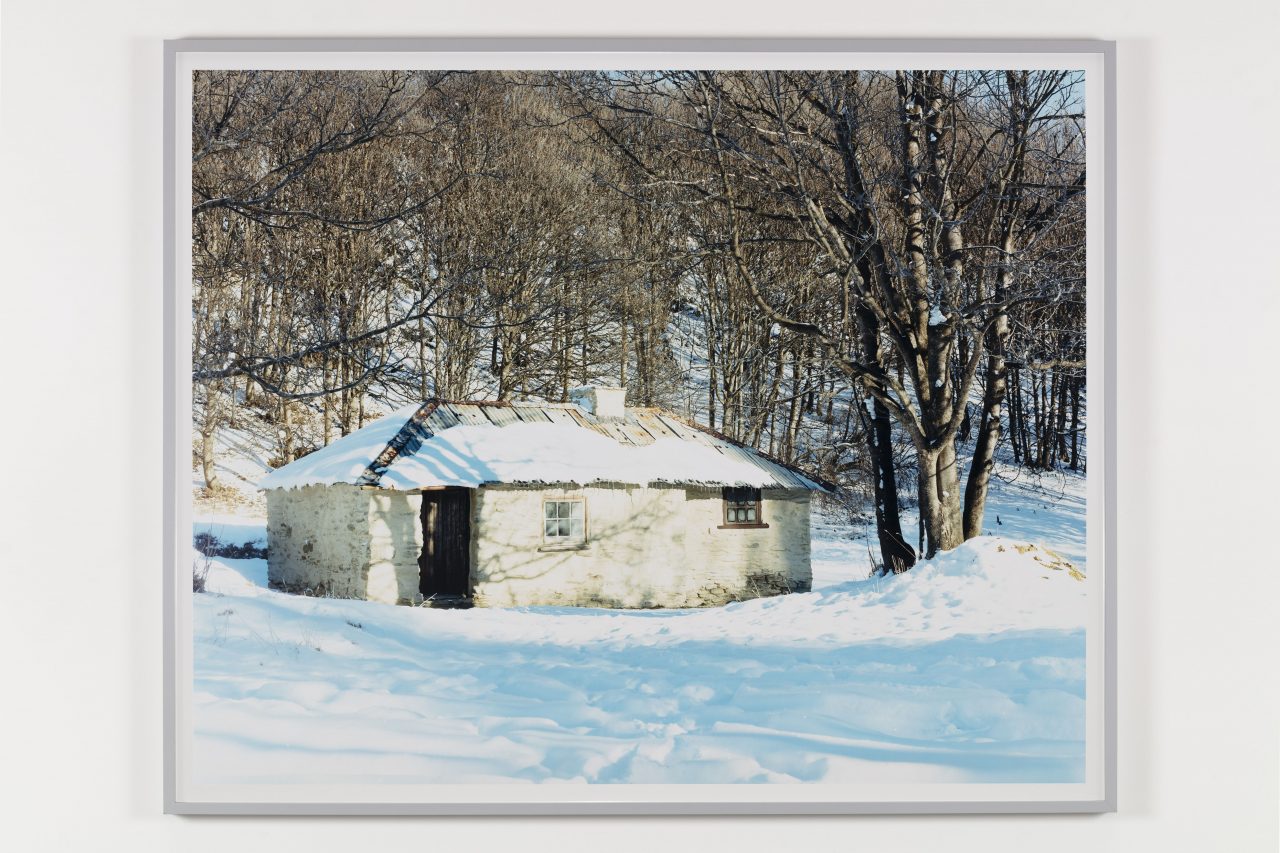

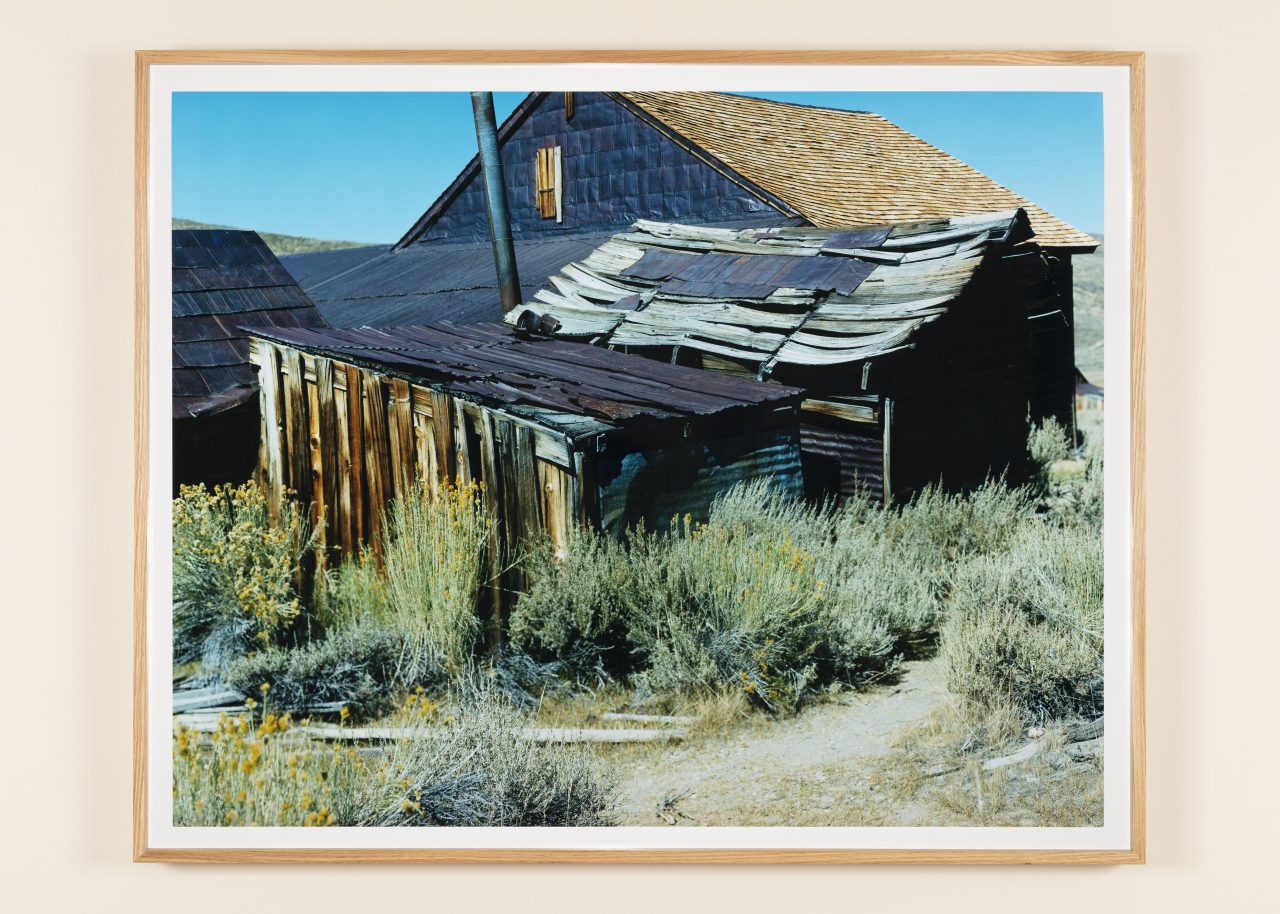

In these “remote” places that seem to have been cut off from civilization, relics of the gold rush era still remain in the natural landscape, even after more than 100 years have passed. Sometimes it’s the wreckage of a vintage cabin. Sometimes it’s the remains of vintage cabins, other times it’s giant gears used to generate more power. These objects, which could be called “junk,” have lost their original meaning when they were in use and are now just pieces of metal that cannot be returned to nature.

The perception of history is sometimes very strange. When I stand in front of the relics of the gold rush, I feel as if the place where I stand, the present, is slowly melting away. Just as the space itself becomes distorted around an object with strong gravity, even the sense of time seems to be distorted around the remnants of the gold rush. At such times, history itself, which I had thought of as a skin that could be peeled off piece by piece, seemed to connect to the surface of the present like the core of an onion.

I don’t know if there is such a thing as “the present of history,” but Gold Rush’s works are documentaries in the present tense of a certain history. His style of searching for “junk” while holding a large vintage camera may be a quirky style of documentation, but to the untrained eye, he is probably just an anachronist. However, for me, the style of documenting with a large bellows dark box set up on a tripod, as if I were half inside the camera, suits me. Because this one body is still an important medium to know this world.